I find it hard even to envision a crowd of this size. I can see thirty. That’s a school class, bunched together for some awkward activity like a photo shoot. I have a decent idea of what 200 people in a lecture hall look like. I know I have seen close to 20,000 people in one space at the Boston Garden. But even so, how relate “one in ten thousand” to my hopes and fears? No clue.

One in ten thousand is the incidence of a four-leaf clover. I never found one, but doing so seems likely to me. If I sit in a patch of clovers — I look.

Ten thousand is the number of bird species in the world. In the human brain, each neuron is connected to other neurons in about ten thousand different ways. One in ten thousand is also the incidence of Prader−Willi syndrome, a genetic disorder that causes insatiable appetite and obesity. So while finding the four-leaf clover seems likely, I’ve never knowingly met anyone with Prader−Willi syndrome and telling apart ten thousand birds or imagining one thousand connections seems insurmountable.

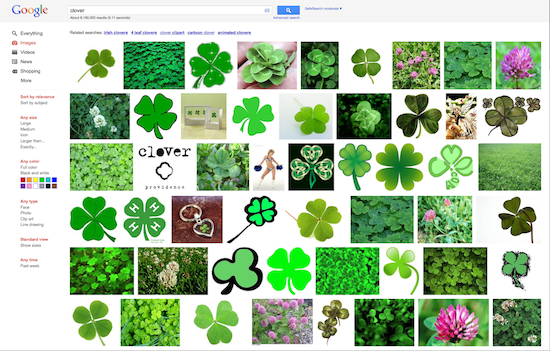

So why is this? The properties of clover play a role, of course. Clovers are smaller and move around less than humans, they come in only two kinds (clover with four leaves and clovers with other number of leaves) and are visible to the eye. But my illusion of ease for finding a four-leafer, has probably more to do with this Google image search for “clover”…

The ubiquity of images and stories of the four-leaf clover makes them seem likely. Just like celebrity-ridden media makes teenagers believe they are likely to grow up famous (rare) and drama-drenched features on child abducting strangers (even rarer) make parents afraid to open the door.

Most narratives focus on the crisis and the exceptions. This shapes the common idea of the world in more subtle ways than “the world is bad but I will win the lottery.” (While in reality, in America, things are getting harder on an interpersonal and financial level, while the world is getting less, not more, violent). In the book Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television, published in 1978, former adman Jerry Mander lays out the world view of television viewers, which includes detailed beliefs such as cops and lawyers being much more common real world-professions than they were.

But is it possible to show things in context, more true to the way they are, without putting the audience to sleep? Is it possible to find a sustainable storytelling of the normal?

Fortunately — as Chris shows here with 9,999 three-leaf clovers — the normal sometimes behaves in wondrously surprising ways.

We’d love to hear what you’re working on, what you’re curious about, and what messy data problems we can help you solve. Drop us a line at hello@fathom.info, or you can subscribe to our newsletter for updates.